An informative listing of every DMB song in history, complete with a printable bracket of the best of the best in the band’s catalog.

Read moreEvery Dave Matthews Band song, ranked

Getty Images

Your Custom Text Here

Getty Images

An informative listing of every DMB song in history, complete with a printable bracket of the best of the best in the band’s catalog.

Read more

A lot of variety and no consensus on which record(s) came out on top. That makes for a fun year — with some unexpected LPs emerging as favorites.

Read more

Given the much-appreciated feedback on my pair of podcasts with Steve Lillywhite, who famously produced Dave Matthews Band's three biggest and best records, I had an impulse to follow up with a commentary on the band's ninth LP, Come Tomorrow, which was released June 8.

***

Dave Matthews says he no longer gives a fuck. This is, in part, a lie. As you can see in that linked video, Matthews speaks to turning 50 last year, and at that point, crossing the Rubicon when it came to, well, not giving a fuck.

But in terms of catering to the wants and wishes of his long-lasting, ardent fans, Matthews mostly hasn't given a fuck in ages. He is all too aware of the devoted-if-sometimes-disenchanted following he's developed in the past 20-25 years. In some ways, he seems needlessly self-imprisoned by what music he writes/plays, and who he should be doing that for.

Matthews has been battling this for more than half his career, dating back to the decision to punt on the widely lauded (but unfinished and never intended for public consumption) Lillywhite Sessions in favor of the hastily assembled Everyday, which features some of the best and worst pop songwriting he's ever done.

While DMB is — somewhat shockingly, but also deservingly — in the midst of a retrospective reevaluation from some mainstream outlets, all the while there's been a considerable faction that's stuck by the band's creative legitimacy and Matthews' inventive songwriting, which dates back to the fruitful beginnings of his career. These hardcores have done so in spite of variable returns on albums and diminishing rewards on setlists via deep cuts that showcase the group at its most vital and enviable.

Matthews' songwriting, while still occasionally offering up some huge wins ("Lying in the Hands of God," "Squirm," "Why I Am," "Broken Things" and "Snow Outside" are all A-level material from the band's two prior records), has fluctuated with much more volatility over much of the past 17 years. (This is reasonable.)

The band has a treasure chest of songs yet to get album treatment. Some of those songs have been played live. Many more are locked in the DMB vault; only a privileged few know how many, or how good, or how finished, those tunes are. Come Tomorrow is the public's first peek at what's under the lid. The LP arrives as a 12-years-in-the-making mélange of a record. The 14-track, near-55-minute album is a collection of work that spans multiple studio sessions that date back as far as 2006 to as recently as 2017 (or potentially even into 2018).

It's the most curious DMB album yet because there's not a violin solo to be found (an uncomfortable necessity, and I'll get to that in a minute) and only one brief, eight-bar standalone moment for saxophone. That comes courtesy of Jeff Coffin on "Black and Blue Bird," an airy, constellation-name-dropping number about cosmic humility that got the red-pen treatment in the studio.

Provided to YouTube by Sony Music Entertainment Black And Blue Bird · Dave Matthews Band / 大衛馬修樂團 Come Tomorrow ℗ 2018 Bama Rags Recordings, LLC Released on: 2018-06-08 Soprano Saxophone, Composer, Lyricist: Jeff Coffin Drums: Carter Beauford Composer, Lyricist: David J.

In his revealing interview with Vulture from May, Matthews alludes to previous albums that wound up standing short of his vision. Matthews faults himself in this, citing creative suggestions made by others (seemingly outside the band) and instead of holding firm to what he wanted, he played nice and abstained from putting his foot down. That isn't the case on Come Tomorrow, which is clearly the most self-indulgent album Matthews has ever made. It's a DMB record that includes three songs without the band, including one song that features Matthews playing all the instruments.

The result is "That Girl Is You," a demo-ish experimental track with a high-wire vocal take that, frankly, has no business on a DMB album.

Yet for all of Matthews' supposed newfound conviction in the studio and regarding album decisions, this record finds four cooks in its kitchen — three more than any other DMB album previously. Rob Cavallo, Mark Batson, John Alagia and Rob Evans produced this record. The album benefits from the multi-angled attack at points, but also loses its station because of differing engineering techniques and sonic decisions that got made by different producers in different studios at different stages of the band's career.

The record is a mishmash. "Can’t Stop" has no link with "Here On Out" which has nothing in common with "That Girl Is You" which is a world away from "When I'm Weary" which is five genres removed from "bkdkdkdd," which has nothing to do with anything. The tempting "bkdkdkdd" snippet is BTCS-like: it shows up like an intriguing but uninvited guest and then quickly slips out the door.

And while the songwriting here is arguably the best in totality from Matthews since 2003's Some Devil (fitting, since that is his only solo LP, and CT feels closer to that record than any DMB album), Come Tomorrow is hampered by a few mismatched song inclusions and some head-scratching production decisions. Among them:

There is a potential reason for the record's jumbled tracklist and overall lack of traditional DMB fingerprints when it comes to the band's sound: the allegations against Boyd Tinsley. The former DMB violinist has been accused by of sexually harassing and abusing a prior member of the band Crystal Garden, which Tinsley helped assemble, played in and managed as a side project while with DMB. On Feb . 2, 2018, after DMB's tour (and impending album) had been announced, Tinsley tweeted that he would be taking a hiatus from touring with DMB to focus on his health and family.

More than three months later, Consequence of Sound broke the story on Tinsley's alleged sexual misconduct. Because of that story we now know that less than 24 hours before Tinsley announced his hiatus, his accuser's lawyer issued Tinsley with a demand letter. One action begat the next. Tinsley has denied the allegations. On May 17, and in conjunction with CoS's story, Tinsley's accuser, James Frost-Winn, officially filed a suit in Washington State "alleging that Tinsley created a 'hostile work environment' where compliance with sex-based demands was tied to the band’s success. The suit seeks $9 million in damages," according to Consequence of Sound's story.

The band quietly dismissed Tinsley in an official/public capacity within 12 hours of the story posting. This came via its PR reps, and only in response to inquiring media outlets who sought comment after CoS published its piece. The band's official statement claimed no knowledge of the accusations against Tinsley prior to the CoS story being published. Tinsley's biography no longer appears on the band's website, and he has not been mentioned, referenced or seen in any album promotion for Come Tomorrow ... with one exception.

Matthews openly discussed Tinsley in his interview with Vulture ran on May 14, which came three days before the CoS story. Here's what he said about Tinsley in that piece:

To get back to the subject of the band: Things had to change after LeRoi passed. Now things have to change again because Boyd’s not around. How difficult is that shift going to be?

I have a deep love for Boyd, and he has to deal with his stuff. In many ways I’m sure it would’ve been a lot easier for him to just say, “I’m good. Let’s go play.” But you can’t just throw yourself away, your wellness away, because you play violin in a band. It doesn’t make any sense to do that.

I follow what you’re saying about why Boyd isn’t around, but how anxious are you about how his absence will affect the music?

I’m used to turning to my right and seeing him going bananas — some days doing it better than other days. You know there’s that idea of genius as something that, like, comes into a room through the window and into a person rather than lives in the person all the time? Sometimes I’d hear Boyd and I’d be like, Holy shit, you are good. Other times it’d be like, Clearly today you left the window closed. But that’s beside the point. We’re all like that. I have terrible nights. The answer is that I don’t know how it’s going to be without him there.

And are there plans for him to come back?

I can’t say, “I can’t wait till he comes back,” because I don’t know what’s going to happen. But right now being away is better for him. Nobody is happy about this situation. Except that we’re happy he can figure some stuff out. I hope he does. But I’m going to miss having that whirling-dervish Adonis-Muppet over there on my right. I know the audience is, too. But we can’t serve that desire.

In writing about/reviewing/grading this album, context with the Tinsley case is significant. And even within that context, we're still lacking answers to important questions surrounding the timeline of this album's finalization. If the band's hand was forced because of the news regarding Tinsley, it makes sense to see the album as is, with a tracklist that isn't quite cohesive because some violin-inclusive songs were left off or updated in the 11th hour to scrub him from certain recordings. (If anything, the album overcomes this to impressive ends.)

The big unknown: If Consequence of Sound's story doesn't get published, is Come Tomorrow a different album than the version that is out now? Is Tinsley on the record for more than just one song? (His only appearance comes buried in the mix on "Idea of You," which also features the late LeRoi Moore, and so it is likely the be the final track on a DMB album that features the five original members.)

It remains to be seen if we'll get answers to these questions. The Tinsley news didn't break until mid-May. By that point, the album surely should have been finished. Are we to believe DMB was going to release a record with so little violin on it? Even with Tinsley's reduced role in the past 8-10 years, that seems a stretch.

No matter the mystery (why certain songs were kept off) or controversy (Tinsley) with this album, and regardless of the six-year gap between releases and the ever-changing economy of the record-buying public, DMB is still one of the most reliable sellers in mainstream music. Come Tomorrow is set to debut at No. 1, marking the seventh straight time that's happened with a DMB album.

With violin scarce and horns pushed to the margins, DMB is missing its signature sound. That doesn't stop Come Tomorrow from being a good LP, though. Even Carter Beauford, who does get a few spots to show off his ridiculous drumming ability, is more restrained on this set than any except the all-time blunder that is 2005's Stand Up, an album universally regarded as far and away DMB's worst. Batson produced that record, but you'd hardly know it based off the Come Tomorrow tracks he was in charge of. Two months ago, if you pulled out "Come On Come On," told DMB fans it was a shelved album cut from the past and asked them to guess the producer, Steve Lillywhite would instantly spring to mind. But no, this is Batson's work, and it fortifies the record. There is some reputation repair here for the most maligned character in DMB history.

The highest peaks on this LP come on the three-song run from "Idea of You" (also Batson-produced) to "Virginia in the Rain" to "Again and Again." From a production-plus-songwriting standpoint, the band hasn't had a triple-track run that strong on an album since 1998's Before These Crowded Streets. The latter two tracks were produced by Cavallo and outclass every single song he did on 2009's Big Whiskey and the GrooGrux King.

"Virginia in the Rain" has a case as one of the 15 best studio cuts of the band's career, and "Again and Again" isn't too far behind it. The ironic but compelling part: Matthews doesn't play guitar on either of them.

"Virginia in the Rain" is the longest song on the record, bringing credence once again to the notion that this band's studio strengths are best served when they're allowed to stretch out the sketch. Some Radiohead vibes on this one. The chorus doesn’t uplift the song so much as it settles it. Play this on headphones on a warm summer night and you'll feel the fireflies floating behind your head.

Provided to YouTube by Sony Music Entertainment Virginia In The Rain · Dave Matthews Band / 大衛馬修樂團 Come Tomorrow ℗ 2018 Bama Rags Recordings, LLC Released on: 2018-06-08 Drums, Composer, Lyricist: Carter Beauford Producer: Rob Cavallo Bass, Composer, Lyricist: Stefan Lessard Composer, Lyricist: David J.

Tim Reynolds is wonderfully extra extraterrestrial on "Virginia," but it's Stefan Lessard who comes through biggest. Lessard, whose bass playing has always been underrated, has never been so vital on a record as he is here. It's nice to hear him expand, pinch and curve a lot of these songs. This album is Matthews' creative statement, but Lessard's performance is the most valuable on the LP. (Digression: Moore gets that distinction on Under the Table and Dreaming and Stand Up; Beauford wins Crash and Streets; Matthews takes the title on Everyday, Busted Stuff and Away From the World; Reynolds on GrooGrux.)

If there is an unforeseen/nostalgic alt-rock revival set to arrive in the next half-decade, let the record reflect that DMB got into the water early. "She" is the fifth track on the album and the punch in the arm the record needs after the loopy "That Girl is You." It sounds like a Pearl Jam knockoff, yet it works because of the brawny chorus that clicks naturally in and out of the verse. This record overall is elevated, if not saved, by its abundance of good-to-great choruses: "Samurai Cop," "Idea of You," "She," "Virginia in the Rain," "Again and Again," "Come On Come On" and "Do You Remember" all bring the hooks. In many cases, those songs are driven by Matthews' riffs, and the melodies on most of them are self-assured. Much of DMB’s best work starts with these foundations. On Come Tomorrow, they're conspicuously missing solo or play-under accompaniment.

You really wonder what kind of magic Moore could have dropped on some of these tunes, particularly "Do You Remember."

Had the band opted to give Coffin and trumpeter Rashawn Ross a little more space to shine, and slightly extended the endings on "Again and Again," "Black and Blue Bird" and "Come On Come On," the record would've been better for it. (Because of the musicianship in this group, the shorter-is-better approach usually doesn't benefit their work in the studio.) Even Reynolds, who dating back to Crash is a consistently great studio performer, feels tucked under the sheets: He only appears on seven tracks, but is deployed best on "Cop," "Virginia," and slickly dodges in step with Lessard on "Again and Again."

It's because of the lack of soloing and bridges and outros that the album moves along with solid pace; the record feels like the second-fastest listen in DMB's catalogue, only behind 2001's Everyday. Sure, "Can’t Stop" is a reworked 2006 tune that is a carnival of unnecessary (lyrically, it's among Matthews' worst), but the run from "She" up through "Do You Remember" (only Dave Matthews could write a song like this and only Carter Beauford could write the perfect drum backbeat to stitch it together) is a dynamic pan across eight tracks and 32-plus minutes that ensures the album will at worst be placed alongside (if not eventually a nudge above?) GrooGrux and 2012's Away From the World in the pantheon of DMB records.

Twenty-seven years into a Hall of Fame career, that's a win.

GRADE: B-minus.

“Man … this was a lot harder than I thought it was going to be.”

You said it, Mike White.

That’s what Mike (head coach at Florida) told me as we hit a certain heavy point in our conversation, an interview I was having with him about Torrey Ward, one of the first really close friends he had in coaching.

The Illinois State plane crash story is the most difficult one I’ve ever had to write, for both emotional and structural reasons. On the emotional side, here’s some perspective: I interviewed 17 people over the course of four consecutive days, tallying more than 22 hours worth of interviews. Most of the people wound up crying (and why shouldn’t they). The two who were the most emotive are not related to the crash victims.

The sound I could not get out of my head after I had my interview with her was the voice of Kathy Davis, the beloved coroner.

“Don’t hurt them. Please don’t hurt those families.”

Davis was not in my original plan for the story. But she was referenced so often, so lovingly by so many, I knew I had to speak with her. And I’m so glad I did. From her eye-witness account of the crash site (most of which I did not include in the story) to her tender bedside manner, she was the thread that connected the wounded on that day. McClean County is lucky to have Kathy Davis as its coroner. She is incredible.

Every time I put ambition into writing a feature, I question my motivations. Why do I want to write this story? Does it serve a bigger purpose or touch on themes larger than what’s on the surface? Have I ever written something like this before? Am I challenging myself? Who am I serving by writing the story, and are my desires to write something coming from a place that’s not selfish as a writer? It always must be about the story and the people involved in it. Always.

For me, extensive features are given justness when you can truly say to yourself that you’re writing a story not for yourself, but for the people the story is about and the general public that is owed a chance to be educated, or informed, or enlightened on a particular subject or event. Writing this story was not fun. I wouldn’t want to do it again. But I don’t have any regrets about doing it, and I’m proud of the final product. I think I’m a better writer for it. I tried to balance the tug of the story — a plane crash happens, and almost two years later there still is no resolution about how the plane crashed; that is disturbing but interesting — with the way so many families were changed forever.

I was also bothered by the fact the crash happened and it was almost immediately forgotten about by most outside of Bloomington-Normal.

My No. 1 concern in writing this story was putting together a complete, lucid account of what these families have been through, but not doing it in an exploitive way. It’s easy to default to purple writing when tragedy is heavy. I do hope I was able to avoid this type of frame. To get a sense of who these widows were, I needed to know where they were, what they were doing, where their lives were before they lost their husbands and fiancés. I have endless respect and gratitude for these incredible women who agreed to speak for this story. It has been hard to stop thinking about them, and the men they’ve lost, since I began working on the piece.

I reported and wrote the story over the course of nine days. (NOT RECOMMENDED.) I didn’t plan for it to be like that, but given the workload of the college basketball season and a tardy desire to get this story out, to not wait for the two-year anniversary, it made for a stressful process. Ultimately, my feelings are immaterial, but that is a little bit of a peek behind the undertaking.

There were items from my reporting that I did want to include, but did not make it into the final cut. Two people I interviewed who are not quoted in the piece: Mike White, and Tennessee State coach Dana Ford. After ISU coach Dan Muller met with his team early on the morning of April 7, he first called Dana, then he called Mike. Dana played at Illinois State and was on Muller’s staff for two years with Torrey. Dana knew everyone on the plane except the pilot and the plane’s owner, Scott Bittner. I didn’t have to pry Dana for quotes. I let him just roll. It’s impossible to put on the page the earnestness of his voice as he spoke about these friends he lost.

“You couldn’t find a bigger supporter,” Ford said of Terry Stralow, who he met when he was 18. “Aaron Leetch was an awesome boss to have. A superstar. Jason Jones is one of the only fans who texted about recruiting, always wanted to know about recruiting and knowing about the players. Andy Butler, good gracious, you couldn’t find a bigger ISU fan. Just a lovable guy. He’d bend over backward for Redbird athletics. These were the blueboods of ISU basketball fans. These guys didn’t miss a game. They would do anything. These were good, quality men. I’m talking about cream of the crop. Husbands, fathers, fans through the ups and downs. Treated the kids awesome, the coaches great.”

Ford was at home when he got the call.

“It was dream-like. One of the very few experiences in my life, very out of body, and I knew a majority of the guys on that plane.”

Dana and Mike, like many coaches in the business, went to Torrey’s funeral. He was the only person in the crash who was able to have an open casket. But Dana and Mike did not approach the body. The reality of Torrey’s death was still too raw for them.

“I didn’t want that to be my last image of him,” Dana said. “It was just so, so not Torrey. Torrey is bubbly, lively, bouncing off the walls. That’s just not Torrey. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen Torrey with this eyes closed. I just couldn’t. That could not be my last image of him.”

Said White: “It was hard enough, the news was just tough enough to take. I guess I just wanted to remember him how I remembered him.”

Dana’s family developed a very close relationship with Torrey’s mother, Janice (who was my second interview for this story and was amazing to speak with). Torrey was always a big deal in Birmingham. Since his death, the school has established a scholarship in his name. Dana also included these thoughts about Muller.

“Dan, he’s helped me grow so much. Dan has a soft heart. Dan’s a good, good man. His toughness through all of this, I couldn’t imagine as a head coach, talk about losing someone on your staff and losing some of your biggest boosters, keeping all of that together. Last year didn’t end quite as well and to keep that thing intact, those guys intact, they just won the league for the first time since 1998. That’s called leadership, man. That’s what it is. What do they say? Anybody can drive a boat but so few can navigate. Where are we going? We’re going somewhere, but are you navigating or are you driving?”

Muller has been the navigator. That program is at its highest point since he was there—as a player. That was the late 1990s. Will add this: Illinois State should not earn an at-large bid this year because the program, and Bloomington-Normal, have gone through this tragedy. But if the Redbirds got in, it would be an incredibly powerful thing for that town.

As for White, he met Torrey when recruiting inner-city Birmingham. Ward’s first year working in college basketball came at Jacksonville State. And yes, how about this: Jacksonville State made the NCAA Tournament this year, its first time ever. So Ward meets White (they’re both in their mid-20s at this point), and he lives with White—free of rent—for a year. Sleeps in the living room. Ward was doing grunt work merely to get into the business. Torrey made such a strong impression on then-Jacksonville State coach Mike LaPlante that he earned an assistant spot when White left J-State for Ole Miss. Eventually, Ward and White were both working under Andy Kennedy in Oxford.

“Torrey was always the life of the party, the life of anything he was involved with,” White said. “He had as magnetic a smile and as magnetic a personality as anyone I’ve been around. He was as likable a persona as I’ve ever met, and I don’t say that because he’s passed. He had a special talent in recruiting. If Torrey spent a couple of minutes with you, you were going to walk away and say, man, I really like that guy. Work ethic, intelligent, never had a bad day, always making you laugh, pulling pranks on you. He’s hiding under my desk, biting me on the leg.”

Some of the best anecdotes you’ll get from head coaches is them telling you stories about their days dangling on the low rungs on the ladder, their hard-luck years as grad assistants, video guys or ops guys. White remembered it snowing in Oxford one year and, well, here he is telling the story.

“I pull up to the office, I’m walking into the practice facility,” and as White is telling the story, he starts cracking up. “All of the sudden I just start getting beaned all over the body. There’s Torrey, behind a wall built, an artillery of snowballs. I’ve got snow in my eyes, can’t see, and then he just tackles me right there in the open. …. I would tell people all the the time there may be a better coach, a more experienced guy, but Torrey is the most talented guy I’ve ever worked with,” Mike said. “His upside was through the roof. His net was so wide. He was consumed with it. He loved people and it made him a natural for this business.”

There is also a group of men affected by this who are somewhat overlooked: the players Ward coached and recruited. Melissa Muller described them as in a “zombie-like state” in the moments after Dan told the team in the locker room that Torrey was gone. Tony Wills remembered Torrey as a guy who convinced him not to quit during his freshman year. Wills was lost. Torrey reined him in. He also remembered practices being more quiet. Torrey had a booming voice, and the boom was gone in the gym.

“That’s when it started to hurt even more,” Wills said.

Paris Lee said the news didn’t register with him at first. He thought Muller was trying to say Ward was merely injured in a plane crash. He asked Muller, in front of everyone, if Torrey was still alive, then turned his back and faced his locker when he realized what had happened.

“It didn’t seem real,” Lee said. “Everything did not seem real to me around that time.”

The other element of this, that I did not go into too much detail in the story, is what an incredible job ISU athletic director Larry Lyons and his staff did that day, that week, and for a long time thereafter. This was a crisis, and it was handled magnificently, according to everyone I spoke with. The families were not bothered by the media. In the early parts of the morning, Larry was scrambling early to determine who was on the flight.

Had Lyons not taken a business trip the week prior, it is possible he would have been on that flight instead of Aaron Leetch. Lyons described Lindsay Leetch as “the most incredible person.” And others described Janice Ward, and Joan Stralow, and Kathy Davis, and the others in similar terms.

“My staff, at least the people in the original planning, were so good,” Lyons said. “They put their grief on a shelf for several days.”

Lyons was effusive in his praise for Aaron Leetch. It was Lyons who recruited Leetch back to Normal, after Leetch left for a couple of years to better his resume by taking a job as a D-III athletic director. At the ACC tournament this week, I had someone approach me—who I never met—to express how great a person and good a guy within the world of college athletics that Aaron Leetch was.

There is more good to come from Illinois State, but I can’t disclose what. ISU community has been tremendous, from getting local business owners to put up their work, hours and money for memorials, to the way others simply left flowers for the families for months and months and months. People doing yard work, unprompted, for some. This story was a blip nationally, but I wanted to put on the page how this horrific event is still part of the everyweek experience for thousands in that area. And now the two-year anniversary is approaching, and Project 7 will bring goodness to that area, prompting random acts of kindness, seven of them, by each of the seven widows.

If you’ve made the time to read this, and the story, I thank you. There are seven wives and fiancees who don’t get to take a day off from this. There are so many young children who are are growing up without their dads now. If any of you ever read this, just know that it was my honor to do those men justice.

I recently had the lucky opportunity to be a fly on the wall for Guster's 25th anniversary show at the Beacon Theater. I wrote a feature on that night and the band's history for Relix. It was an amazing experience that I'll forever be thankful for. I mean, check this: Sidestage during Satellite. Felt like I could reach out and touch the kit.

Sidestage at the Beacon 25th anniversary show on Nov. 25.

As usual, plenty of content didn't make it into the article. As usual, I want to put a lot of that material -- all of it on the record -- on the Internet rather than let it float in the dark forever. So here are some tidbits, quotes, nuggets, facts and random one-offs. I know there are Guster diehards out there. This is for you.

-- First off, a new Guster LP should be on the market by the end of 2017. It wouldn't be a surprise to see a couple of candidates make their live debuts at Guster's four-night run in Boston in January.

Via lead singer Ryan Miller: "We have a handful of really, really good songs. The quality control, it takes us a long time because we don’t just put out the first thing, and sometimes thing have to gestate for a while. We have eight songs we’ve written in the past six months, and four of them are OK, and four of them are great. The idea is you try and not inundate people with stuff that isn’t the best that you can do. I think we’ll start recording relatively soon. We kind of need to to keep the momentum of the band. I will be super bummed if we don’t have an album by the end of ’17.”

He added: "Every record has been really important for us to not make the record we made before."

-- The group appears to be in a great spot in terms of knowing the rhythms of the band, the wants. The desire to keep going is strong. That wasn't as certain five years ago, even three years ago.

“We’re in a really awesome zone where we’re actively choosing to be in this band and balancing our outside lives,” Adam Gardner said. “The music and this band is still at the forefront. ... Every time we get together, no matter how long, there’s always good stuff that comes out that we’re excited about. I’ve never walked away from a writing session with the band where I felt like nothing happened.”

-- The first song the band wrote (and performed live)? Fall In Two.

-- Most underrated Guster songs, by fans? From the perspective of the band, these tunes qualify: Hang On, Expectation, Do What You Want, Two at a Time. (My opinion: C'mon is a top-15 Guster song all time, and the band should play it every other show.)

.

-- Brian Rosenworcel, drummer/percussionist, on the band's need to change its style in order to them to literally continue to be able to make music: "I couldn’t say we had a gameplan for longevity, but looking back it, you’ve gotta change, you've gotta reinvent yourself, otherwise you get stagnant. After three albums we had a huge following in part because of our instrumentation, then we decided, very controversially, to shed that instrumentation. It was a bold decision. I'm agood percussionist and an average drummer, so it was humbling in some ways but was a good decision to open up our minds. I needed it for my own longevity. My hands were in really rough shape from like 1999-2002. The shows were becoming way too abusive. It was my own fault. I played a brand of percussion that was untrained and hitting cymbals and snare drums that are not meant to be hit with your hands."

-- Multi-instrumentalist Joe Pisapia changed what Guster was. After joining the band full-time in 2003, he left in 2010. I asked the members about that amicable separation.

"I don’t think I saw it coming," Rosenworcel said. "He told us after some show in Pittsburgh, right when Easy Wonderful was about to come out. It was hard on me, but Joe is my friend and I want what’s best for him. But when you look at the fact that he wrote an album with KD Lang. He wrote the songs, he played the songs and sang the songs with her, and the album meant so much to him, and therefore he wants to go on the road and support it. Whereas Easy Wonderful was such an awful process. It took forever. It wasn’t anything like what his process with KD was like. Then, the two songs that Joe sang [for Easy Wonderful] didn’t make the record. And there’s reasons those songs didn’t make the record -- they didn’t quite fit -- but our relationship with Joe is super strong and super bonded forever. He did things to our music that we needed. I’m very grateful for Joe. I think he’s off the road and those days are pretty much over. ... Joe always played the hardest part on every song; he was the one real musician in our band — and when he goes away, it’s when you take out of the 3-4-5 hitters, like we have nothing. Luke (Reynolds) is equally capable of playing all the difficult parts."

-- Regarding some of the tough times in the studio, here's what Rosenworcel said about the Goldfly and Easy Wonderful sessions and how they compared to Lost and Gone Forever.

"There was a culture in the studio where they rolled their eyes at you if you wanted to experiment with stuff. In particular there was a view of our instrumentation as insufficient. Steve Lillywhite, who is a much better known and loved producer than Steve Lindsey (Goldfly producer), is the opposite. [Lillywhite] built us up and got the best out of us. We worked with producers who have like, I don’t know, tyrannical edge — David Kahne on Easy Wonderful — and it was really hard. It’s really not good for a band to have to suffer through it. I understand producers are artists and are opinionated, and that’s what makes them distinct, and whereas (Evermotion producer) Richard Swift didn't necessarily think he was right 100 percent of the time. I could respect that. I don’t really know how we ended up in the studio with some of those guys. It wouldn’t happen that way again. We’re too smart to make that mistake. ... You can’t regret that. I look at Goldfly as a missed opportunity. We worked with a producer out in LA that we just had a terrible relationship with, and made that a negative process, and after Parachute, which was wildly successful for us, just being a college band, it sounded disappointing. You could feel it. Whereas some of the songs on there were still pretty good. It didn’t really hurt us, because we came back on the next album."

-- There is a song from the Ganging Up on the Sun sessions entitled "Emily Ivory." It was initially slotted as the "main track," per Rosenworcel, and treated as the best song on the record. Eventually the band soured on it some. Then the lyrics got a rewrite. Then it was scrapped altogether. Now Rosenworcel says it's one of the worst songs the band's ever written and it will probably never see the light of day. This, of course, makes me want to hear it all the more.

-- The album that sounded the most different as a final product vs. the expected sound going in? This one shocked me: Parachute.

-- States Guster has yet to play: Hawaii, Alaska, South Dakota.

-- The band hates the gaps between studio albums' releases. For Keep It Together, Ganging Up on the Sun and Easy Wonderful, the reason those albums came out months after the original plan was due to record execs asking for different songs with different sounds. This frustrated the band every time (and is partly why they are now running their own label), but these mandates did wind up producing some terrific tunes. Songs that were born as a function of record company demands for rewrites: Hang On, Careful, Homecoming King, Amsterdam, Keep It Together, Lightning Rod, One Man Wrecking Machine, Do You Love Me, This Could All Be Yours, What You Call Love. Satellite, which the band wanted to be the lead single off Ganging, was rejected by the suits. (Ooops!)

-- Gardner's involvement, passion and professionalism when it comes to running Reverb can't be overstated. He's helped changed the mindset of a lot of bands and people in the music business, specifically when it comes to touring with a responsible mindset for being environmentally aware. He's gone to Washington, D.C. and pushed the cause to politicians. Being a member of Guster is 1A, and running Reverb is 1B.

"I'm super proud of what Lauren, my wife, and I started and the team we’ve built here at Reverb and the passion they have. It’s amazing. To me, it adds meaning to what I’m doing in Guster too. They feed each other. The more Guster’s out there, the better it is for Reverb."

-- Regarding Gardner, I had to ask him about a dynamic that's changed in Guster. For the past decade, there's been one or two songs that he's sung lead on. When Guster formed, he sang lead more than Miller. A big draw to Guster's sound is how great those two fellas' voices sound together. So why the change, and could the new record have more Adam in the forefront?

"A lot of this just has to do with melodies," he said. "It has lots do with who wrote what and what works with each song. A lot of my writing role within the band has to do with harmonic structure and feel. And a lot of the melodies tend to pop out of Ryan’s mouth. It just kind of naturally, the melodies lend itself to his voice. Ramona is one of my favorite songs, but I did not write that melody. Ryan did. So it really just comes down to what works best. Do You Love Me, a lot of those phrasings, I wrote a lot of that, and it’s hard to tell who wrote what because we just explode ideas in a room together. I don’t think it’s specifically like, 'We don’t want Adam to sing' or 'I don’t want to sing anymore.' It's more, where do melodies come from? I do miss some of the intricate harmony stuff and I do hope there’s more of that in the future. Sometimes it’s hard to do that when you want to focus so much on melody. A lot of it this is letting go of your ego."

-- Found it interesting that Miller didn't have a wide knowledge of music when he got to college. He didn't discover albums by The Cure, The Grateful Dead, Van Morrison, The Beach Boys, New Order, etc. until college -- and even after. Now, from my view, those bands, and a lot of avant garde acts from the past 30 years, feel like they have their colors in his paints.

-- I asked Miller: You all seem like politically knowledgeable people, but that hasn’t really been reflected — too much — in your music. Intentional? Do you find it hard to write political or environmental without cringing?

"Adam has been a hero to me on the activism tip, watching how he even approached the environmental thing. He says, 'You just tell them it’s here and it’s available to them. This is what we’re passionate about personally, but you can take it or leave it.' Of course I respect the fuck out of bands like Rage Against the Machine or Radiohead, who made politics part of the music, but as a primary songwriter I’ve never been drawn to that. We don’t define our music by our politics, and that was never a conscious decision.”

-- The band has had frustrations over the years at a lack of widespread critical acclaim and falling short of making it to a next level of success and fame.

“Sometimes it’s hard to watch,” Gardner said. “It’s like, ‘Jeez, how come that hasn’t happened for us?’”

They have thankfulness for where they are, without question, but they've also seen everyone from Maroon 5 to John Mayer to the Avett Brothers to fun. open for them ... then go on to be much bigger acts. (There have also been dozens upon dozens of bands who came and went, not even making a dent, and the band is very aware of that, too.)

"On the level that people ask me what I do and I say that I'm a musician and that’s not a hedge and I’ve made my professional life as a musician and I support my family with playing music, it’s fucking incredible," Miller said. "I don't think I would’ve had the audacity to say that even as a college kid. Yes, that’s insane. But we call it the reverse curse. 'Open up for us and you’ll win a Grammy.' That has been, on some level, as a band that has ambitions to have as many people connect with us as possible, has been extremely frustrating. We haven’t gotten critical nods, and in retrospect I don’t know if we deserve them. So there’s been a ton of frustration kind of watching it play out but as we’ve gotten older and were realize what place our music does hold of people, again, it is very humbling and something we take very seriously. Would I want to be selling out three nights Red Rocks instead of having to open up? Sure. And would I have liked to have a couple platinum records instead of no platinum records? Absolutely. But that said, for every band that’s ahead of us, there’s thousand and thousands that are probably better than us and are behind us. I don’t wish we were Vertical Horizon, who had a big hit song and kind of went away."

One more video: Mona Lisa, the best song off Parachute.

Beacon Theater, November 2016

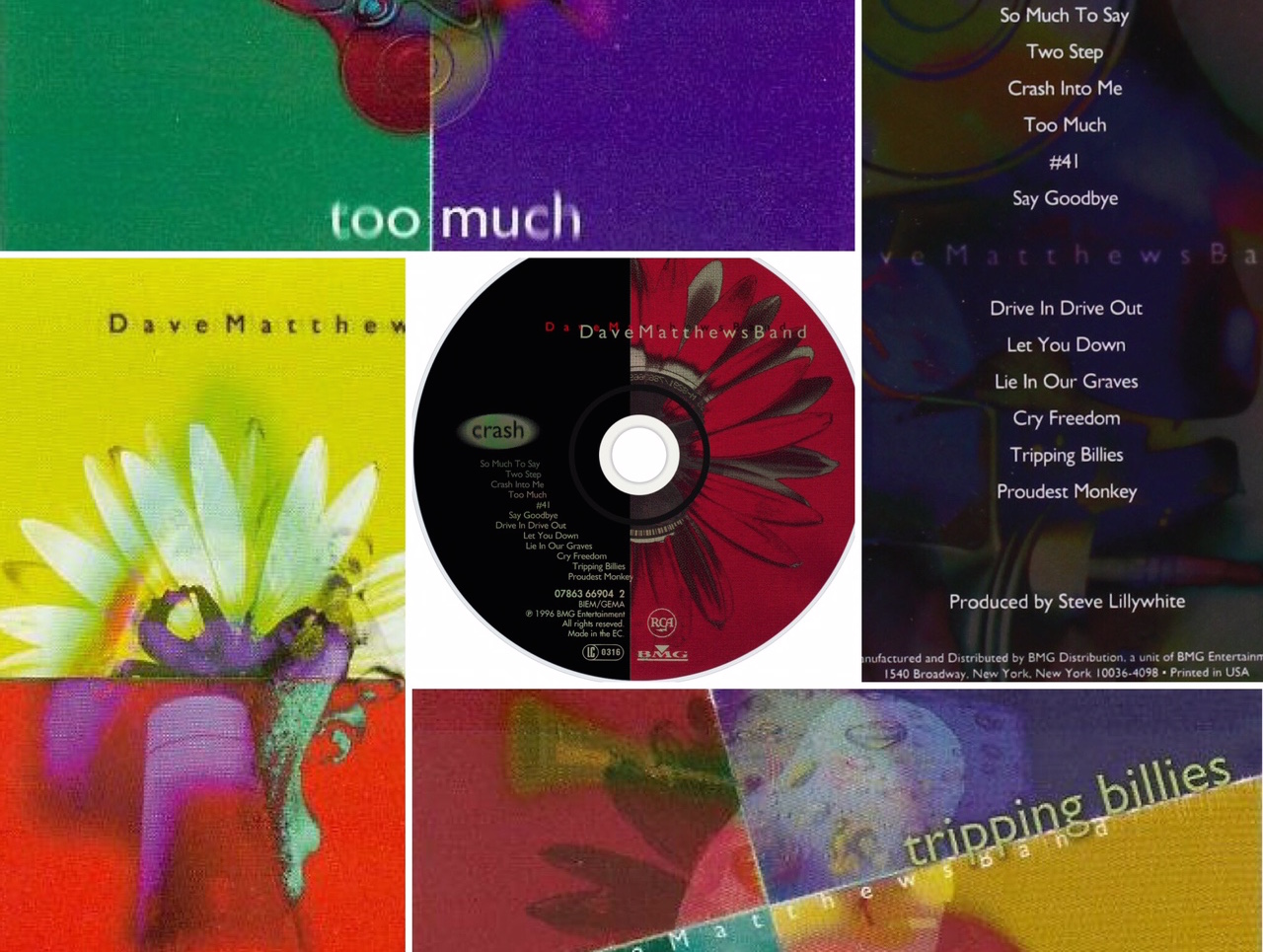

Over at Relix, I have a piece up on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the release of Crash, DMB's immensely successful 1996 LP. It was a really fun retrospective to write, but in speaking with the man who produced that record, Steve Lillywhite, I collected a number of quotes and anecdotes for the story that didn't fit into piece. Being that there's still an army of DMB hardcores out there, I wanted to post those tidbits here. Lillywhite is a joy to talk to. Very funny, someone who can digress (this is for the better) and a guy who's, in general, a great interview subject. Here's what hit the cutting room floor.

— It’s taken for granted now, but Lillywhite wasn’t even a given to produce Crash, even after the success of UTTAD. He was in the midst of a divorce, and would randomly get updates over in England that UTTAD was doing well. He had no distinct expectation of ever working with the band again after UTTAD. There was also an unusual element in play: Tom Lord-Alge mixed most of UTTAD after Lillywhite finished (this was RCA's request), so for all he knew, Lord-Alge could've been the guy for Crash.

On getting the call to come back: “In those days, if someone mixes your album, it’s like they’re coming in to save it, not coming in as just another part of the job. I come from a world where the producer’s job is to record it and see it right through to the end with the mixing. What happened with Under the Table was they needed someone to come in and mix it, and I felt a little bit upset. … And when I heard the final mixes I thought, Oh, that’s not how I would have done it. But, you know, that’s always going to be the case. I’m a control freak, you know. If I’m not there doing it then it’s not right. Maybe one of my weaknesses, who knows.

“Pete (Robinson) and Bruce (Flohr), to their credit, they didn’t say to me, ‘We need Tom Lord-Alge to mix this album. They said to me, ‘Steve, it’s your choice.’ So I went, 'OK.' So, we’re getting near the end of the album. He’s in New York, I’m in New York. Let’s try me in there with him to mix three or four songs. I instigated him to come and mix these songs, but I mixed most of the album myself at the shitty little studio at Greene St., where Tom had this up-do-date studio. I had the $10 studio and he had the $100 studio. But, in reality, you listen to the album you can’t tell who did what song, and I can’t even remember which songs I did. And some of that was because I was in there when he was mixing, so it was sort of my print on the whole album.”

— Lillywhite mentioned the album was “relatively easy to record” and “the band loved Woodstock.” All the music was recorded in Woodstock, but then they had 6-8 weeks of vocal work and overdubbing with sax at Greene St. Studio in NYC, which closed in the early 2000s but was one of the legendary hip-hop studios of the '80s and '90s. Lillywhite remembered a blizzard hitting at one point during the recording/overdubbing. Dave and LeRoi would intermittently come and go to lay down their parts.

“To be honest, it was not a great studio," he said. "It was a great vibe, but as a studio, it was pretty rough-and-ready.”

— Lillywhite told me he listened to the album the night before our interview, and it was basically the first time he listened to the record in full in almost 20 years. I thought that was pretty surprising. It was also surreal to be talking to him while we both listened back to the studio cut of "#41." Just a cool moment. He said he forgot about segueing 41 into Say Goodbye, and when I explained him how rare it is for the band to replicate that in concert, he got a real kick out of it.

I asked what he felt as he listened to this record after so many years in between: “I felt sort of sad with LeRoi (Moore) not being here. I felt wistful remembering back, especially in the middle section of Lie In Our Graves. I loved doing that. And that chord progression, when they do it live it goes to a whole different place. But I was very happy, and it took me back. We used to have this thing where we did a lot of overdubbing in the Barn. It was a rehearsal room, but we turned it into a recording room for overdubbing."

On Friday nights they’d get a loads of people from the village of Woodstock, and after the locals left the pubs, Lillywhite would invite groups of them back to the Barn. As for Lie In Our Graves, I asked if the crowd and band knew they were being recorded for a section of LIOG. He said no.

"We'd do some work and listen to songs and party down, and I just recorded everyone having a good time. They didn’t know they were being recorded. ... Nothing is an accident. Everything that’s there has been approved by my ears and placed there in a specific place because it works. Perhaps I overdid some of the things on the album. There’s one or two themes happening at the same time that maybe I should have had less. Sometimes with hooks, I had too many hooks. Like on "So Much to Say," on the little chorus bits.”

— Most of what you hear on Crash, in terms of sound, themes and concepts of it, were mostly conjured by Lillywhite after he met up with the band at Woodstock.

“I don’t do homework," he said. "I’m not a big fan of homework. I do believe in me in a recording studio with a bunch of talented people who all have no egos involved, whose only purpose is to make the best recording, then the chance of some magical things happening are possible. And I know this because it has happened in my life more than once. There has to be — no one’s ego must get in the way. This is where things get out of hand. I didn’t listen to the songs before I went. I got on a plane, met them in Woodstock, and said, ‘What have we got?’”

— The one thing he did suggest prior to getting to the studio: "For instance, take LeRoi. I told him to bring every instrument you have to the studio. Whereas Under the Table had a lot of lovely soprano saxophone, and it was very pretty and very beautiful, and I didn’t tell him, I just gave him the idea that I wanted something different. LeRoi suggested to bring his baritone, and that became almost the signature for the album on the saxophone front. I loved saying to the band, 'Let’s push ourselves.' And they are fantastic musicians, but I was the leader of the sound. And really, it was job definition separate. The band would play and I would mold and steer. Anything to do with that was all me, for better or worse. It was not necessarily 100 percent successful. It gave the album certain psychedelic qualities in some places."

— He laughed as he recalled loving the challenge of pushing Tim Reynolds and Moore, who he called “great foils” for his ways of working in the studio. He added: “With Boyd, you never knew where the nuggets of gold were."

"It’s all down to trust," he said. "They trusted me to lead to steer the ship, and that’s very important."

DMB touring for the Crash album. From left: Stefan Lessard, Dave Matthews, LeRoi Moore performing at the Blockbuster Pavillion in Los Angeles on July 27, 1996. (Getty Images)

— As for the track listing, Steve said that was all him and Dave, just as it was on UTTAD, and that the band “didn’t have so much of an opinion about that.” The album was recoded at 24-tracks. There were four were songs — "Get In Line," "#36," "True Reflections" and "Help Myself" — that were also played at the studio, but they were laid down as bare skeletons and then rejected. Lillywhite said the songs weren't close to being finished and so they were never heavily considered. (To be fair, "Reflections" was definitely a finished product at the time; it just didn't make the cut, and it's for the betterment of the record it was pushed off.)

Last bit here: I had him go song-by-song and asked him questions and what things stood out about each song or recording them. A lot of it was fun rambling, so I've pared down his quotes and just tossed in an anecdote or two on each.

Two Step: The cue for the song's outro — Beuaford's double-kick 1-2-3-4/1-2-3-4 — which has been a staple for two decades now, was created in the studio somewhat by accident. Carter and Steve liked it, as it happened somewhat spontaneously. Lillywhite: "Carter was like, 'That’s great! That’s great! Let’s work on that.' I think he maybe did it one time, and from there I wanted to turn it into a part.”

Re: Dave's vocals on the song: "Every time Dave did a lead vocal I would play the vocal, and he would do things before the real singing started, and I would go through them and mold and build up this choral thing. But it was never Dave saying, ‘I want to do this.’ And he’d sing and I’d go, ‘Maybe I’ll keep that, maybe I won’t.’"

#41: Lillywhite said loved that siren-like sax intro to start, and really appreciated the layering that sets up the first verse. He said this song had a slew of edits in it, and when he heard it they all came rushing back. He added that no one would ever notice where they are, but he heard them immediately. I'd long wondered what the sound that pops in at the 3:18/3:19 mark of the song is and why it was placed there. Turns out it's Moore's flute, and Lillywhite used it as a quick preview of the flute jam to follow after the chorus.

“Musically, I think it’s great," he said. "I’ve got NO IDEA what Dave’s singing about, and I’m not sure he does either.”

He said he did remember Dave’s litigious battle in the mid-'90s and possible references to that within the song. He also shared this, which I agree with: "I think when Dave started to put his lyrics more like 'I’m going to write lyrics,' I think that was not as good as when it was when his mind was empty and things would come out. Later on in his career he would try and write lyrics, whereas early on his career he would just sing and words would come out. And I think maybe that’s what fans love about the early songs. It’s more freeform, more free-flowing."

Drive In Drive Out: I asked Steve if Dave played the Gibson Chet Atkins in recording this song. He couldn't verify. We talked how we loved how the song had back-to-back bridges.

"It’s got a very progressive sound but also sounds like Soundgarden in there. That’s what I loved about them, there was no real structure."

On Moore's "improvised" lines: "What LeRoi’s favorite thing was to use cartoon themes as his saxophone lines. So, when he went [Steve sings second bridge line from DIDO] that’s from a Warner Bros or Tom and Jerry, or something like that, and if you listen to a lot of his sax lines, he would play something from a cartoon, but he’d play it over DMB songs, which sounded very … so you wouldn’t recognize it. He was a sneaky old bird, LeRoi was."

He has regrets with one part of this song: Beauford rubs the skin of the drums with his finger and creating the “oooohm” sound in between every break on the DIDO outro. I mentioned to him how often I'd heard this song, yet only really caught that recently. "Here’s the thing," he said, "You listened to the song 200 times and you never heard it. My argument would be, if I only brought them in halfway through the outdo, you would’ve heard it every time."

A connection between the album's hardest and softest songs: Listen carefully as DIDO ends, and those rubs on the toms is how "Let You Down" starts.

Let You Down: “When I listened to that yesterday I, maybe for personal reasons, but I really enjoyed it. Dave’s voice is so loud in the mix, and I made sure he was right in your ear. Because he sung so quiet that I thought it’d be nice to have a quiet voice really loud. The whistling solo was something, I remember Bruce Flohr saying ‘Trying a whistling solo.’ I know a lot of people have criticized the solo, but I don’t think it’s so bad. And LeRoi was a great whistler. For me, 'Sitting on the Dock of the Bay' has this great whistling on the end. And I thought if we could get some nice feeling, yeah, I think it’s OK."

The plan, absolutely, is for Steve and I to connect again in 2018 to do a piece on the band's best record, Before These Crowded Streets. That was the first album he ever produced while entirely sober.

"And it’s funny," he said. "When I came out of rehab and we did Before These Crowded Streets, that was a whole different way of looking at music."

The reaction at the buzzer of George Mason's upset over No. 1 UConn in the Elite Eight. (Getty Images)

I had so much fun exhaustively reporting out the 10-year anniversary story of the 2006 George Mason team that shocked the world and changed the tournament forever when it reached the Final Four. If you've not yet gotten a chance to read it, stop reading here, go check that out, then circle back around for the bonus cuts.

The story is long as is (more than 9,990 words), but if even still, I had to cut a lot in order to keep the pace and tension of the piece going. There are elements and anecdotes to that GMU team I found interesting enough that I wanted to share and just do an info/quote dump. So let's just get on with it.

LAMAR BUTLER: Played on the same AAU team as Delonte West, and won a state title in 2000 at Oxon Hill (Md.) alongside a future Georgetown centerpiece and NBA lottery pick, Mike Sweetney. Larrañaga recruited Butler, and his childhood best friend who grew on on the same street, Phil Goss. During an informal visit in 2000 Larrañaga told them both in person he had one scholarship available, so the first guy to verbally commit would get that scholarship. Butler committed a few days later, before ever taking an official visit. He chose Mason over Xavier. The decision angered Butler's father. After he committed, then-GMU assistant Bill Courtney told Butler he was so happy he never took his scheduled visit to Xavier -- because he knew Butler would have committed had he taken the trip out to Cincinnati.

Goss would go on to star at Drexel but did not play in an NCAA Tournament.

Butler and his father cried as they hugged at center court on March 26, 2006, minutes after Mason upset Connecticut and just before Butler was interviewed by Bill Raftery.

TONY SKINN: Was not recruited out of Tacoma Park, Md., by any D-I school. His road to Mason was longer and more serpentine than any other player on that '06 team. Skinn landed at Mason after a stint at Blinn College in Brenham, Texas, then a stop at Hagerstown, in Maryland, where he was putting up nearly 30 points per game. That was in 2002, when Courtney (now the coach at Cornell) and Eric Konkol (now the coach at Louisiana Tech, where Skinn is an assistant) saw him. Skinn was out of his element early at Mason. During his first workout he was so confused doing basic footwork and skill drills, the coaches asked him if he'd done any basic fundamental work at his previous two JuCo stops. He hadn't.

JAI LEWIS: Grew up in Aberdeen, Md., and picked Mason over fellow Colonial Athletic Conference teams VCU and Drexel. Larrañaga was worried at the prospect of having to face Lewis for four years in the league, and wondered if he'd pick Philadelphia-based Drexel because Lewis' girlfriend at the time attended Villanova. But Mason's location -- close enough to home, but far enough away -- was a determining factor.

WILL THOMAS: He was almost passed over by the staff until Konkol took another look at him at an AAU tournament and was convinced he'd be perfect at the 4 in Larrañaga's offense. Larrañaga didn't see him until months later, and within five minutes of watching him play, he had to have him on the team. Like Butler, Thomas was convinced to commit before ever taking official visits to other schools. He picked GMU over the likes of Providence, Richmond and Ohio State. At 6-foot-8, he was Mason's tallest player that season. Thomas was extremely quiet. He didn't speak much when he was younger either. His mother would give him puzzles and he sit and solve them.

FOLARIN CAMPBELL: Was the best recruit of the five Larrañaga chased. I explain in the story that he was basically setting his sights on Georgetown—and then Georgetown pulled its offer.

GABE NORWOOD: Was similar to Skinn in that he couldn't get D-I offers. His dad is a D-I football coach and has worked at Richmond, Navy, Texas Tech, Penn State, Baylor and is currently defensive coordinator at Tulsa. Norwood only wound up at Mason after his team won a state title in Pennsylvania -- and they discovered tapes of him that this father dropped off at GMU a year earlier.

Where are they now? Butler, 32, lives in D.C. after spending a five-year overseas career in Turkey (twice), the Czech Republic and Libya. He has his own clothing apparel/uniforms/equipment business. Lewis -- who played for six years in Israel, the Phillipines and Japan -- is now 33 and works as a behavior interventionist, helping troubled young people deal with behavioral development. Skinn, 33, went viral with a vicious dunk back in 2010 while playing overseas. He played on the Nigerian national team that was in the 2012 Olympics. Thomas, Campbell and Gabe Norwood are still playing overseas. Thomas is in Spain, Campbell in Poland and Norwood in the Philippines. I spoke to those three over Skype while reporting the story. Norwood gave me more than an hour of his time while chatting in a cafe in Manila with his wife. He's lived there since 2009. He has two children, as does Campbell, who married his high school sweetheart.

To a man, they all say that George Mason run has been something overseas teammates have asked them about with each stop. That '06 Final Four really did put that school on the map globally.

I couldn't work in just how important Eric Konkol and Bill Courtney were, so I have to say it here. Basically, Chris Caputo -- who was an assistant on the '06 Mason team -- was at first a low-level assistant. He worked camps and did the grunt work behind the scenes. He was the guy who first got to know and develop relationships with Folarin Campbell and Will Thomas. Then Konkol and Courtney ran recruitment of those players. But both those guys took jobs elsewhere just before the '05-06 season. They were an integral part of that Final Four team yet did not get to sit on the bench. They missed out on the party but basically baked the cake. Also, Caputo was going to leave Mason to work for the Hoop Group, but when Konkol left to take a job at Hopkins High School in 2005, Caputo got his chance to join the staff. Scott Cherry was previously an assistant at GMU, then went to Tennessee Tech for a year, but got the offer to come back once Bill Courtney left to be an assistant at Providence.

-- Larrañaga continually asked then-Creighton coach Dana Altman to come play at George Mason. Altman kept saying no. Altman was afraid of criticism for scheduling a small school like GMU. Finally, he said he'd take the game if Notre Dame and Ohio State wouldn't agree to play Creighton. They didn't, so in September of '05, Altman and Larrañaga sign the contract. Creighton romps GMU, and it becomes the game that changes how GMU assembled its starting five and played its defense.

-- Mason lost in OT at Wake Forest and on a last-second shot at Mississippi State. The team felt it got jobbed by the refs at Wake, while Norwood still blames the MSU loss on himself for a bad inbounds pass near the end of the game.

-- Jai Lewis on why Will Thomas was to credit for his senior season: "Going against Will in practice every day, that was tough enough. Once will came in as a freshman, he helped me raise the level of my game because i didn't want him to take my spot. What people don't know is, after every rebound every point either of us missed in getting a double-double, we did pushups after every game."

-- "VCU was always crazy because they sat their band right next to our bench. Their band director would be on us and yelling at our bench. We'd be like, man, don't you have to direct the band? He was crazy -- but we won." -- Gabe Norwood

-- What's lost a bit with Mason's run is how Jai Lewis (6-6, 290 pounds at that point) basically had no business playing as much he did. He remembers being very frustrated. He played out the final three weeks of the regular season on two injured ankles, requiring intense cold-water therapy before and after games to keep him halfway healthy.

-- After the Skinn punch debacle, Caputo was nervous and didn’t want to be around the campus whatsoever. He went as far as to recruit near the Mexican border, in Cochise, Arizona. He remembers Skinn’s punch being played over and over on ESPN. The reason why Mason and Larrañaga were so serious about having so much fun in the tournament was because the team had to wait a week to find out of it was getting in, and that was a very long week.

-- There was controversy with Mason getting in because Tom O'Connor, the AD, was also on the selection committee. Craig Littlepage being the committee chair, also introduced an element ripe for conspiracy theorists. Littlepage told me he did not speak with Larrañaga until after the Final Four because "as committee chair I wanted to make sure I was as objective as anyone could be over the circumstances. I wasn't cheering for or against George Mason. I wasn't cheering for or against any other team."

-- Loved this anecdote. So Will Thomas was a quiet dude, but in the days before the MSU game, it got strange. He was also the only guy on the team not clearly having fun. Caputo's quote was: "He was very ornery all week. Didn't like the new sneakers, the new sweatsuits. 'I don't like the pancakes at breakfast. This sucks.'" So the coaches started to worry. Larrañaga called his friend, the sports psychologist, Bob Rotella, who spoke to the team in October, and asked what he should do, that he "wanted to kill" Thomas for hurting the team's vibe. Rotella told him to leave Thomas alone, that he was gearing himself up for Michigan State. If he went at Thomas and Thomas got angry, it could make matters worse. So they let it be ... and Thomas just went off for 18 and 14 and killed Paul Davis on MSU. I asked Thomas to confirm this story, and he did.

"They were extra slim. That was before slim-cut was in style," he said of the sweatsuits, laughing now. "I was upset."

-- A quote from Izzo I kept when transcribing but cut from the story: "What I remember most is disappointment of course, because we had a good team, but all the people kind of laughing [at George Mason]. And then it's North Carolina and then UConn and the beat went on. I remember at the Final Four it was a big topic of conversation. I got caught up in the euphoria and all the excitement out there with that run."

-- Gabe Norwood: "One of the biggest memories for me was, my freshman year, we played at UNC. I'm awestruck walking into the Dean Dome, and Sean May is on the other side, and Jai is straight killing him. It was mutal them going back and forth. Seeing Jai competing on that level on the big stage inspired me to be better."

-- Mark Turgeon on the RPI and the Valley teams gaming the system: "We tried to schedule teams that we thought we could beat but thought would win a lot of games and would have a chance to win their leagues. You did that a lot. I even scheduled a DIvision II so it wouldn't count against my RPI."

-- Larrañaga told me he wasn't confident his team would've beaten Tennessee in the Sweet 16. UT got knocked off by Wichita State. And the reason WSU beat the Vols? Here's Turgeon: :"We matched up well with Tennessee but they had a mid-major lineup. They had four guards around a center, who was slight. They were fast and pressed. We were lucky to win, but I felt we matched up with that team. What helped us in that game was, Tom Davis (coached) at Drake, and Tennessee ran the system because Bruce Pearl (Tennessee's coach) worked for Tom Davis. So we saw the system a lot over the years. We played Drake twice a year."

-- If you're curious which assistant had the lead scout for the UConn game: Caputo. In fact, Caputo was the lead scout on every game in that tournament.

-- Larrañaga said the idea that the UConn game was the biggest of his career "never entered" his mind.

-- Lamar Butler on playing in D.C. "The fans, you don't know even notice them once the ball goes up. Looking back, it wasn't on the court, it was off the court that we won. That team is like family. You saw one of us, you saw all of us. Parties or whatever, we were always together. I remember going to the grocery store and guys going out to their vehicles and saying, 'Hey, you need a ride?'"

-- Can't emphasize enough how ridiculous it is that a team like George Mason, which lacked a true big man, ran the same damn play about 25 times in a row -- and UConn did not do anything about it. Scott Cherry: "The bench, we just kept sitting there and asking, 'Why are they not double-teaming him?' Jai wasn't very big. He had long arms, great hands and great footwork. He's got that butt on him. He could back you down and get to the rim, and has his length to score. And Will was automatic using his left hand. If they took that away, he had a great drop-step. The double teams weren't coming and they never made an adjustment."

-- Butler on UConn tying at the end of regulation: "I remember walking to the huddle being so tired, but we've got five more minutes. At no point did I sense any lack of urgency from our team. Nobody's feeling sorry for us about losing the game."

-- James Johnson: "The look that I saw in those guys' eyes ... I don't know if anyone would have beaten us that night. Never once did our guys look fatigued or like, This is too much."

-- Folarin Campbell on the fallaway he hit over Rudy Gay in OT to give GMU a four-point lead. "That was the biggest shot I've ever made in my college and professional career. It was a play that broke down. I was on the right-hand side. Rudy was guarding me and I remember Coach L behind me saying, 'Take him.' He's 6-9, I'm 6-4, and I swished it. When I released it everything felt good."

-- Many GMU players commented on UConn's lack of chemistry. Some of that is quoted in the story. Here's Will Thomas: "I think they played like that the whole season. They weren't really a team. Collectively they had a good team on paper, but I don't think they were completely together. If you really watched them, you could tell they weren't playing together, they were just, 'Well, we're out here together, so let's run the play."

Butler and Norwood told me three UConn players admitted to them later in life that the Huskies' locker room was not close, and that the loss to GMU was something that still bothered them.

-- Calhoun told me not his '06 club, but instead his 1994-95 team (Ray Allen, Donny Marshall) that lost as a No. 2 seed to UCLA in the Elite Eight was his best group not to reach a Final Four.

-- Larrañaga got one of the nets; Lewis got the other.

-- So Billy Packer made a huge stink about George Mason's inclusion to begin with. Then, at GMU's first night in Indy at the Final Four, the team goes out to have a luxurious dinner at the famous St. Elmo's Steak House. Jim Nantz and Packer happened to be in the house.

"Larrañaga said, 'Why don't you go down there and apologize to those kids," Caputo said. "Nantz couldn't have been nicer. Pure class."

-- Mason's story dovetailed with the tremendous story of Jason McElwain, the autistic teen whose 3-point barrage in February turned him into a national story. McElwain was with them on the team bus and attended shootaround. Larrañaga and McElwain had a 3-point shooting contest; McElwain beat him, 10-9.

-- Larrañaga's son, who was living in Naples, Italy, flew across the world the night/morning before the Florida game. Jim met his grandson, James Larrañaga III, for the first time when he was brought to Jim's hotel room shortly before they got on the bus for the national semifinal. JL3 was born almost two months before, on Feb. 9, 2006.

-- By the time you get to a Final Four, details matter and schedules go haywire. Larrañaga said biggest obstacle was the schedule. "It entirely messed up our routine because of how far the locker rooms were for the court. We had to out for national anthem, back to the locker room, back out for the tip. I'm in my suit and dress shoes, but the security people say, you gotta get back out on the court. It was so far a walk, that you had to run."

-- Players told me their adrenaline was so high, they ran to the court -- but their locker rooms were on the opposite side at the RCA Dome.

"My god, we dead-sprinted from the locker room," Norwood said. "They had the VIP party behind one of the bleachers. I remember being tired by the time we got on the court to warm up. We honestly just dead-sprinted 80 yards to get into layup lines. I was trying to catch my breath."

-- Norwood on the experience in Indy: "Overwhelmed is probably the best word. From the heightened security at the hotel all of the sudden, to people asking us to sign stuff and seeing it on eBay within 20 minutes. To be a 20-year-old kid signing an autograph for little kids who look up for you all of a sudden, it was really cool."

-- Jai Lewis: "Playing Florida? I think we played well against the Florida. They had everything they needed to win. I honestly believe that if we could play that game again, I think we could come out victorious. The game was close until about 10 minutes [to go]."

-- Norwood said Larrañaga's rule for not wearing headphones paid off in this respect: "He wanted us to get to know the Greeks, the club members, student government. We built friendships outside the world of sports on campus, and I think that helped with support the whole way through. There were people who went to Dayton, people who helped drive and set up the buses to go to Indianapolis. These people were our friends. These are people I still talk to now."

-- Finally, this quote from Butler stood out to me: "The experience was crazy. It's hard to leave your hotel. Autographs. People everywhere. Then you're playing in a dome, and I'd never played in a dome. That was our first experience. My first shot was an airball in shootaround. It was a different backdrop, the perception was off. I remember some kids wanted our autographs to put it on eBay. I remember walking one time with a hood on and just wanting to walk, to have people not recognize me."

Reporting on this story was a thrill. I think it's one of the best stories in the history of college basketball, and I wonder if we'll ever again have the true sense of surprise that Mason provided us. Butler, VCU and Wichita State's Final Four runs were so fun and great too, but they did not match the shock of what Mason did, when it became the first mid-major team in the modern era to redefine what double-digit seeds could do in the NCAAs.

GMU players still believe they'd have made the national title if they played LSU or UCLA instead of Florida. (Getty Images)